Storytelling is an ancient tradition that has existed for eons; its origins lost in the swirling mists of time but its intricate threads still intrinsically woven into every culture of this world. Were the scenes from the first story verbally described in a homely alcove set deep inside a cave, offering protection from the elements and the frightening unknowns of the night? Were they enthusiastically performed around a glowing fire in a ceremony to appease the ancestral spirits resident in the starry night sky? Were they meticulously depicted on the rough walls of ancient caves? Did the tradition of storytelling develop as a crucial aspect in the passing on of learned knowledge, not only between ancient compatriots but down through the generations as a way of ensuring the survival of age-old traditions and beliefs? Throughout history my family has been meticulous at keeping written records of their life stories, offering their descendants a glimpse into the by-gone eras of the past and allowing a fragment of my ancestors to continue on through the ages. Nowadays relating a story can offer comfort in a difficult situation, entertain through the embellished nature of tall tales and fables, and strengthen an argument or opinion or, in my case, be used as a bargaining chip to convince me the bedtimes of childhood were for my own good.

The mere mention of a journey into the enchanted world of dragons and giants, pirates and pixies would make the long drawn-out episode of coaxing me out of the pool less frustrating for my parents, stories being my favourite part of the daily bedtime ritual. Even though the mystical creatures depicted on the colourful pages of storybooks easily captivated my overactive imagination, my absolute favourite story was not fiction at all but a real-life tale filled with its own brand of enchantment and picked up over the years from overheard conversations, forming out of the mists of speculation. It’s hard to pinpoint the very first time that I ever heard this story; I have just always been aware of its existence and because my grandfather was an unassuming man and not one for grandstanding, it wasn’t until I asked him directly that he sat down and described to me the events of that summer. It must have left a substantial impression as it is one of the defining moments that ignited my passion for nature and directed me onto the path of my chosen field of study.

The distinctive dorsal fin of an Indo-Pacific humpback dolphin (Sousa chinensis) photographed in Algoa Bay, Port Elizabeth

Set in the cool waters of Fish Hoek Bay (forming part of the greater False Bay region of Cape Town) during the lazy summer days of 1953 my Grandfather had the unique experience of encountering and interacting with two bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncates), aptly although slightly unoriginally, named “Fish” and “Hoek”. My interest in the story was recently reaffirmed when a maroon, and slightly dishevelled, attaché case was unceremoniously dumped on my desk with a suggestion from my dad that the contents would help combat the writer’s block that has annoyingly been plaguing me. The contents turned out to be a time capsule of family history; documents dating back centuries and describing the life of our Scottish ancestors in some far-flung castle, newspaper articles detailing the rise and remarkable moments of my great-uncle’s relationship with the equine star, “Sea Cottage”, and a handful of very special photographs that re-energised my cranky old brain, stirring up the beginnings of an exciting idea.

I spent hours, while studying in Port Elizabeth, watching the dolphins passing the beach almost like clockwork every morning and afternoon

Over the next few days I immersed myself in the carefully folded, yellowing pages of the accompanying articles that were nestled in amongst news items outlining a very detailed program for the Coronation, the placements of warships in our country’s ports, a supposedly outrageous price hike demanded by Nepalese porters traipsing Western luggage through the once forbidden territory (1953 being the year that Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary first summited Mount Everest) and next to an alarming advert for Anadin, described as being for “women’s ‘special’ problems”! One article that did grab my attention was titled “Her ‘eyes’ will roam the decks” and referred to a golden Labrador named Sheena being the first dog allowed to roam the decks of MV Carnarvon Castle in the capacity of a guide dog. She was only the second of her kind in South Africa and provided support to a Mrs Evans who was returning from England after undergoing training with Sheena. This was a key event in the establishment of the first guide-dog training school here in South Africa… what is most astonishing is that this occurred only 63 years ago!

A pod of dolphins on the hunt holds the capacity to entertain even the most cynical among us

As usual researching a new topic has led me on many digressions into the unknown, a diverging maze of intriguing paths that ultimately reconnect to form the essential thread of the greater story. Between poring over photographs, questionable newspaper articles and fascinating correspondence; I explored the myths and legends surrounding these toothy cetaceans, uncovering a history of rare encounters outlined in A Book of Dolphins (Alpers). This book, written by New Zealander Antony Alpers, is worth commenting on as it not only mentions my grandfather and his awesome experience but also directed me to a remarkable 2nd century poem, Halieutica, by Greco-Roman poet Oppian of Anazarbus. This peculiar 3 500 line poem uniquely describes the marine fisher tribes of the deep with startling fascination afforded to the mating rituals of just about every marine species. The poem opens with a beautiful description of ancient fishermen and their connection with the sea;

Over the unknown sea they sail with daring heart and they have beheld the unseen deeps and by their arts have mapped out the measures of the sea, men more than human. In tiny barks they wander obsequious to the stormy winds, their minds ever on the surging waves; always they scan the dark clouds and ever tremble at the blackening tract of sea; no shelter have they from the raging winds nor any defence against the rain nor bulwark against summer heat. Moreover, they shudder at the terrors awful to behold of the grim sea, even the Sea-monsters which encounter them when they traverse the secret places of the deep. No hounds guide the fishers on their seaward path – for the tracks of the swimming tribes are unseen – nor do they see where the fish will encounter them and come within range of capture; for not by one path does the fish travel.

To my delight, Oppian even included a stanza on sea monsters;

The Sea-monsters mighty of limb and huge, the wonders of the sea, heavy with strength invincible, a terror for the eyes to behold and ever armed with deadly rage – many of these there be that roam the spacious seas, where are the unmapped prospects of Poseidon, but few of them come nigh the shore, those only whose weight the beaches can bear and whom the salt water does not fail.

While humans are a terrestrial species, there are some of us that feel an inherent connection to the ocean, are drawn to its energy and are driven to explore its depths. This limitless curiosity enticed my grandfather into the water that summer’s day in 1953; the ocean offering up an incredible encounter that very few people have ever had the chance of experiencing. This insatiable thirst for knowledge of underwater exploration was first sparked at the tender age of thirteen when he received a pair of goggles, introducing him to the wonders of the underwater world and leading him to studiously research the exploits of Captain Jacque-Yves Cousteau, Hans Hass, Captain Phillippe Talliez of the French Navy, Bernard Gorsky and Philippe Diole. By the age of twenty-four he was an accomplished diver, putting him in the ideal position to study the two “visitors from the deep”.

He describes the appearance of the dolphins at Fish Hoek as “so sudden that before one realised, they were swimming amongst the bathers”. While it was not the first time that dolphins had visited the bay, an annual occurrence during the summer months, it was the first time that a pair were seen to break away from the pod and lazily swim in the shallows amongst people. The “slow and gentle” manner in which they moved between the swimmers was one of the many aspects of their behaviour that stood out to him, so much so that he wondered, and later enquired, whether or not they were a previously captive pair. In his neatly sloping script, he describes the high speed acrobatic demonstrations that these two displayed out beyond the backline; “cutting through the water at terrific speeds and leaping clear out of the water as they chased each other about like two young pups let loose in a field”.

Bottlenose dolphins at Pipe in Port Elizabeth

In his notes my grandfather uses the terms “dolphin” and “porpoise” interchangeably, even seeking clarification from the curator at Marine Studios in Florida. A distinction between these two cetacean groups had yet to be defined in 1953, FG Wood responding with a short note, From Pig Fish to Porpoise, in which he outlines the confusion surrounding the terminology. Wood stated that classification within Delphinidae was a hotly debated topic between the American and European zoologists of that time; Europeans citing the small size, blunt head and spade-shaped teeth as defining features of a porpoise and therefore ejecting them from the family. In an effort to clarify the distinction between the two groups, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (2014) currently makes use of the following criteria in concert to define a porpoise; spade-shaped teeth, absence of a beak, triangular dorsal fin, compact and portly body shape and the fact that porpoises tend to be less acrobatic and communicative and more sexually aggressive than dolphins. After much debate, it was confirmed that the two creatures frequenting the shallows at Fish Hoek were a pair of bottlenose dolphins, my grandfather’s copious notes, detailing their appearance, assisting in their ultimate identification. In addition he noted that one of the pair, he assumed a male, had “many large scars on its body especially along its sides, the dorsal fin shows evidence of many teeth marks and the trailing edge of its tail has a ‘V’ shaped piece of flesh missing”.

There is something very special about uncovering someone’s handwritten notes, decades after they scribbled them

The gentle nature of these fascinating creatures intrigued my grandfather so much so that he “decided to attempt to make contact and observe them more closely”. His first encounter with these “visitors from the deep” occurred approximately 100 m offshore after spotting the pod in the middle of the bay one Saturday afternoon. Equipped with a mask, snorkel and flippers he slid into the water off Jager’s Walk and made his way out into the bay. With visibility limited to between six and eight metres, he dived down to 8 m and clapped his hands together in order to create pressure waves while simultaneously making noises with his nose. After approximately four minutes he spotted the familiar sight of two dorsal fins intermittently breaking the surface while making, with some urgency, a beeline towards his position. He states that when the fins were approximately 30 m away from him he dived below the surface and waited with “trepidation and excitement in the eerie silence” which surrounded him for his first encounter with the dolphins in their environment. He later describes the moment that he spotted the creatures appearing out of the inky gloom, silently gliding towards him as he gently floated to the surface, as “one of the most moving and memorable experiences” that he had ever had. The pair approached him and at approximately 4 m away they parted and slowly circled him, examining him for several minutes as he lay on the surface. As they slowly advanced towards him they made and held eye contact, giving my grandfather the “incredible sensation that some sort of communication was trying to take place”.

Their torpedo body shape makes dolphins adept at hunting at great speeds

A few days after their initial encounter, the dolphins were spotted “lazily swimming amongst a group of bathers in the shallows” and as an experiment my grandfather entered the water approximately 50 m from their location and swam out beyond the surf. He repeated the clapping procedure of the previous encounter and watched as the pair broke away from their game and headed in his direction. He observed that when the dolphins finally reached him, they again circled him although appearing to do so in a more relaxed manner than previously, approaching to within an arm’s length. He decided then to reach out and touch one of them. His outstretched fingers made contact with the side of the dolphin, just below its dorsal fin, and to his astonishment the animal stopped moving, quietly lying next to him on the surface while he rubbed his hand along the length of its body. Reflecting on the moment he felt that the dolphin enjoyed the sensation as it rolled over onto its back and allowed him to gently scratch its chest and sides, running his hand over its head, beak and dorsal fin. My grandfather describes the body of the animal as being “very smooth and firm to the touch, it was also beautifully streamlined”. He and these two “visitors from the deep” lay in the calm, cool waters off Fish Hoek Beach for at least ten minutes, as he did so becoming aware of a series of high-pitched squeaks and clicks that could be heard once he submerged his head.

I almost missed an exam to take these photographs of bottlenose dolphins off Shark Rock Pier!

He posed the question of communication and a form of echolocation in a second letter to Marine Studios after witnessing the pair’s behaviour during a red tide event in the bay. With visibility drastically reduced by the red tide, my grandfather tested his theory that they rely on a form of sonar to “warn them of objects in their vicinity”. His notes do however describe him as getting one hell of a fright when a pair of snouts suddenly appeared out of the dirty red murk and in front of his mask! Wood of Marine Studios responded;

Regarding the possibility that they detect objects by means of a sonar mechanism, this is still a moot question. A psychologist at one of our universities has found that certain sounds made by porpoises fulfil the requirements for an echo-ranging system, and my own observations of captive porpoises also suggest that they may use sounds for detecting or even investigating submerged objects, but no one yet has definitely demonstrated that they do.

Over the past sixty years our understanding of cetacean communication has greatly increased, among other discoveries we have found that dolphins do in fact possess excellent eyesight both under and above the water’s surface as well as utilising echolocation. Coincidently, Cousteau was one of the first people to investigate and document echolocation resulting in his book, The Silent World, which was first published on 3 February 1953. It is puzzling that this pioneering information was not mentioned in Wood’s letter to my grandfather in June of the same year.

Bottlenose dolphins surfing the waves at Pipe in Port Elizabeth

My grandfather’s encounters continued on for many months, the dolphins becoming so used to his presence that they even allowed him, on several occasions, to hang on to their dorsal fins while they towed him through the water at a brisk pace for distances of up to 10 m. He made a note of keeping well clear of their powerful tails. It was reported in the Cape Argus (28 March 1953) that at one point my grandfather climbed on to the back of the male while in the shallows and dived down with it to the sea floor where it lay quiet still. He then wrapped both arms around its chest but was not quite able to interlock his fingers as its body was too large. The article goes on to describe how the dolphin blows “great bubbles out of its blowhole, shutting its eyes with a sort of ecstasy when tickled”. The distinct behaviour of one particular encounter with one of the pair puzzled my grandfather and subsequently intrigued me. One evening after work he spotted the pair in the bay, one swimming in the shallows with people while the other investigated an outcrop of rocks. He swam out to where he had spotted the latter individual and dived below the surface spotting the dolphin approximately 4.5 m down on the sea floor and engaging with what he first thought to be seaweed. As he approached the dolphin he observed it “opening and closing its jaws, exposing its many jagged teeth”, immediately stopping him in his tracks. He describes feeling decidedly uncomfortable and preparing to leave when the dolphin slowly turned, gliding towards him, revealing not a piece of seaweed but a large octopus squirming about on the sea floor. After being subjected to close-quarter scrutiny by the dolphin, it suddenly circled back to complete its meal uninterrupted leaving my grandfather feeling uneasy and questioning its behaviour. Was the dolphin warning my grandfather off from a dangerous situation or did the animal view him as competition for his prey?

Bottlenose dolphins photographed from Shark Rock Pier in Port Elizabeth; I always think of my grandfather and his time with “Fish” and “Hoek” when I spot dolphins in the bay

Although the first underwater photograph was taken in 1856 (by pioneering Frenchman Louis Baton), in 1953 underwater photography was in its infancy and a waterproof housing, if obtainable, would have been beyond the means of a young government draughtsman. As my grandfather was eager to document his encounters he devised a plan. He purchased a small Kodak box camera with a fixed focus and shutter speed and a Kodak 127 film along with a pair of strong but soft rubber gloves and two glass lenses (as used in a battery operated torch). After cutting off the glove fingers he loaded the camera with spool and placed it inside the rubber glove, creating a waterproof seal with one of the lenses and the glove’s cuff. Similarly he inserted the other lens in front of the camera, sealing the housing by stretching the rubber over the glass. To ensure that the housing was in fact watertight, he cut two rings from the discarded fingers and stretched them over the glass. Due to the malleability of the gloves, the camera controls could be easily operated. At the first opportunity he swam off the rocks at Jager’s Walk and out into the bay to attempt to photograph the pair. He described his encounter as follows;

Once in position I called the dolphins by clapping my hands together while the watertight camera floated next to me. From the surface I could see the dolphins approaching, just before they reached me I dived below the surface and waited camera at the ready as they appeared before me. I took several photographs as they circled and floated beside me in the water. It was difficult to be sure that I had in fact photographed the dolphins as I had no means of using the view finder of the camera effectively under the prevailing circumstances.

After waiting a couple of days for the processing to be completed, he was ecstatic with the results especially when the difficult conditions were taken into account. And so began the correspondence. My grandfather’s encounters with “Fish” and “Hoek” were first publicly documented in an article that appeared in the Cape Times (7 March 1953), which was followed closely by an article in Johannesburg edition of the Sunday Times (8 March 1953). Both articles follow a similar thread by outlining key encounters between him and the dolphins. The Sunday Times however includes an interesting comment that the Fish Hoek Town Council would be approaching the Cape Administrator in an attempt to legally provide protection for the dolphins. Although protection was only achieved in South Africa in 1973 under the legislation stipulated in the Sea Fisheries Act; “protect dolphins from killing, capture and harassment” in the then Cape Province, South Africa’s regulations to protect cetaceans remain amongst the strictest in the world. In 1991 we became the first country to protect the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), a threatened species still being hunted in numerous countries worldwide. On 28 March 1953 the Cape Argus printed an article, Tickle a Porpoise and it Purrs, the title itself of a scientifically questionable nature. The article was headed by one of my grandfather’s underwater photographs but with an alarming twist. Not only did the newspaper print the photograph upside down but, using a pencil, the dolphin’s eye was redefined to better suit the new orientation while its beak was split in two to form an open mouth! It has to be considered that this was probably the first photograph most people in South Africa had seen of a dolphin, never mind one underwater.

This photograph appeared in the Cape Argus (28 March 1953)

One of two remaining photographs taken with my grandfather’s MacGyver-style underwater camera (DJ Sivewright)

The photograph that made it across the world (DJ Sivewright)

The hatchet-job carried out on my grandfather’s photograph and printed in the Cape Argus (28 March 1953)

On 27 May 1953 my grandfather received a response from Die Afrikaanse Kinderensiklopedie stating that while they were fascinated with the unique photograph sent to them of the dolphin, they expressed regret at not being able to include it in their encyclopaedia as it would not have “reproduced good enough” for publication. A similar response was received three years later from the Assistant Editor, PB Brown, of Popular Photography Magazine based in London. While they also regretted not being able to print the photograph, they described it as “most unusual” and “a class apart from the usual type of readers’ picture” while also congratulating my grandfather on his “enterprise in waterproofing” his camera and “attempting such a subject”.

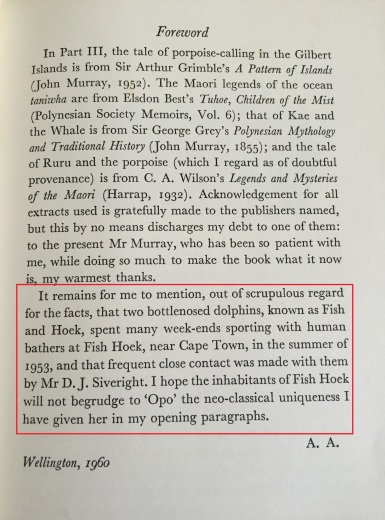

Four years after his encounters with “Fish” and “Hoek” my grandfather received an Aerogramme from Antony Alpers; a biographer, journalist and mythologist from Christchurch in New Zealand. Alpers was completing a book about dolphins, the writing of which was prompted by the episode of a friendly dolphin that frequented the Hokianga Harbour the previous year. During his research for the project, Alpers was in contact with Marine Studios and in particular the curator, Wood, who sent Alpers a copy of my grandfather’s 1953 letter detailing his encounters. In his book Alpers lays claim to the fact that the episode in Hokianga Harbour was the first well known incident since Pliny in the 2nd century that a wild dolphin interacted with people in such a relaxed nature. Due to the fact that my grandfather’s encounters did not receive worldwide coverage, Alpers could let this statement stand and merely mention “Fish” and “Hoek” in his book’s forward. Either way, this story remains very special to me; reading his words and studying his photographs has instilled in me once again the importance of our oceans and further strengthened my intense fascination with their wonders.

A Book of Dolphins (Antony Alpers) first published in 1960

The highlighted paragraph holds Alpers’ acknowledgement of my grandfather’s encounters

My grandfather ends his story with these words;

After the photographic encounter with the dolphins, I spent many happy hours swimming together with my friends in the sheltered waters of our bay, by now the pair were popularly named “Fish” and “Hoek”. As our holiday season drew to a close with fewer bathers frequenting the beach, so did the appearance of the dolphins become less frequent eventually our dolphin friends disappeared, never to appear again at our beach at Fish Hoek in False Bay. Although a close lookout for these dolphins was maintained over the years no reports were ever made of any further incidents of this nature occurring.

It is therefore easy to believe that nights spent sleeping over at my grandparents’ were marked by a deep sleep filled with vivid dreams; a vibrant mix of mystic beings and genuine creatures, the distinguishing line between fact and fiction becoming a fuzzy blur.

The Dolphins both rejoice in the echoing shores and dwell in the deep seas, and there is no sea without Dolphins; for Poseidon loves them exceedingly… (Oppian).

A pod of dolphins on the hunt in False Bay, Roman Rock Lighthouse in the background

Explore. Dream. Discover.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Thank you to Brian Solwandle, from the Cape Argus archives in Cape Town, who introduced me to microfilm and helped me track down the original article.

REFERENCES

ALPERS A. 1960. A Book of Dolphins. John Murray: London.

NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION (NOAA). 2014. What’s the Difference between Dolphins and Porpoises? [ONLINE] Available at: http://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/dolphin_porpoise.html

SIVEWRIGHT DJ. 1996. Close Encounter with Dolphins in Fish Hoek Bay – 1953.

THAYER B. 2013. Halieutica by Oppian. Harvard University Press: Massachusetts. [ONLINE] Available at: http://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Oppian/Halieutica/1*.html#note2

Absolutely wonderful Sally, gave me goosebumps! You can be proud of your Grandfather.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey thanks Zandri, glad you enjoyed it!! 😀 Yup, he was pretty awesome! 🙂

LikeLike

Fantastic Sally! – I’ve been waiting a long time for this to be recorded – I love how you’ve woven it into a story – I can “hear” my Dad narrating the bits you’ve included – great work!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, that means a lot ☺️ I was worried that his voice would be lost in amongst all the facts and information so I’m really glad that it can still be heard 😊

LikeLike

Fascinating! What a great story! Thank you 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you so much and it’s my pleasure! 🌊😊

LikeLike

Happy memories of swimming with the dolphins in 1963 with Fish Hoek friends , Ken Smith and Doug Wakeford . I can remember is quite clearly . Thanks for this story !

LikeLike

Thank you for your comments, glad you enjoyed it! 🐬 Must have been an incredible experience! We have donated all the original photos, letters and articles to the Fish Hoek Valley Museum

LikeLike